A Study on The Divergence of ESG Ratings

Substantial score dispersion and the low correlation of ESG ratings have been a constant source of bewilderment and criticism. MIT Sloan’s “The Aggregate Confusion Project” finds that the correlation of ESG scores among six prominent ESG assessment agencies was on average 0.61. In comparison, mainstream credit ratings are correlated at 0.92.

It appears that this discrepancy impedes the desire of firms to enhance their ESG performance; the scores communicate mixed signals on the priority for each company, and when seen across assessment agencies, it seems the company must address every possible risk. Let’s look at some of the examples of score divergence between three prominent ESG assessment providers. This information is sourced from their publicly available corporate ESG search tool.

Table of Contents

Why does this happen?

“Your personal values are the best compass for your unique journey.”

This quote summarizes possible reasons why ESG rating scores are different among various rating providers.

Let us try to analyze why the methodologies differ. ESG score providers each have their own proprietary materiality, industry classification, and ESG issues using which they compile their scores, which explains the reasons for the variance, viz.

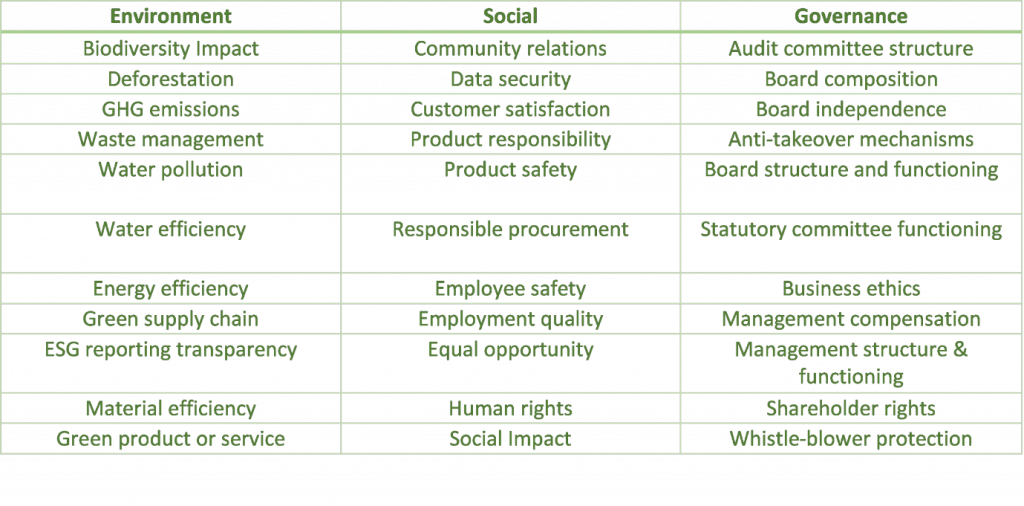

1. Different factors

There are multiple factors that are considered in each of the 3 pillars of environment, social and governance. Below are some of the factors that assessment providers consider.

Variations in assessments are partly attributable to the list of risks considered, how risk management is evaluated, and the assessment provider’s classification of transition and physical risks.

2. Different sector classifications

Sector and industry classifications are often used to identify risk issues that matter. There are two approaches to assigning companies to industries: a production-oriented approach and a market-oriented approach.

Industry classifications like the Global Industry Classification System (GICS), for instance, developed by MSCI and S&P, use a market-oriented approach. GICS consists of four levels. There are 11 sectors, 24 industry groups, 69 industries, and 158 sub-industries. In this case, a company’s main source of income is the most important thing to consider when figuring out what its main business is.

The Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) is operated and managed by FTSE Russell, which also uses a four-tier structure with 11 industries, 20 super sectors, further divided into 45 sectors containing 173 subsectors. The ICB system allocates each company to the subsector that most closely describes the nature of its business. When a company does two or more very different kinds of business, the audited accounts and the directors’ report are used to figure out which one is the most important.

And some, like Ecovadis, use the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC), which was developed by the United Nations Statistics Division. ISIC is a standard classification of economic activities arranged so that entities can be classified according to the activity they carry out. The categories of ISIC at the most detailed level (classes) are delineated according to what is, in most countries, the customary combination of activities described in statistical units and consider the relative importance of the activities included in these classes.

Further divergence may occur for companies with diversified business operations, where they may be classified in different industries by different ESG assessment agencies. As ESG rating agencies often employ different industry classification systems (e.g., GICS, ICB, SICS, etc.), a company’s set of material ESG topics, selected based on the industry classification and evaluated within the rating framework, could vary from one rating agency to another.

3. Different materiality

Materiality in ESG varies from industry to industry and depends on ESG risks and opportunities relevant to a specific sector. For example, patient care and biomedical waste management will be the most important material issues in healthcare, while data security and privacy will be the most important social risks in the retail industry. Divergence can occur when certain indicators or issues are assigned more weight than others by various rating providers. ESG rating agencies have developed their proprietary definitions of materiality.

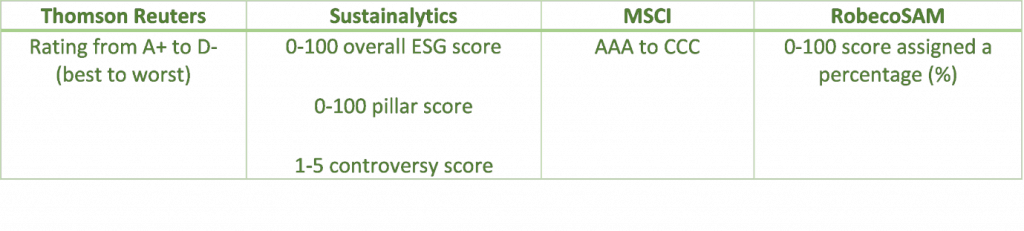

4. Different scales

Each rating provider also reports ESG performance on a different scale, and this makes it difficult to directly compare assessments without normalizing the scores and ratings.

Does this variation invalidate ratings?

As you can see, if each rating provider uses different factors, sector classification, materiality, and scale, then the rating is bound to vary. The question is, can you say divergent scores indicate incorrect assessment of a company or does it point to an evolving assessment landscape? Having a different score or divergent rating is not an issue as:

- The assessment of the risk management approach of a company on material ESG risks remains accurate.

- The impact of a company as gauged through controversies remains valid.

- Inter se performance between companies on the same scale is appropriate.

So what is the issue?

Several empirical studies and research projects show that ESG funds outperform the market while providing downside risk protection. For instance, the research paper published by S. Mohanty, O. Mohanty, and M. Ivanof finds that companies with strong ESG profiles are more competitive than their peers. High ESG-rated companies have lower exposure to systematic risk factors and a lower expected cost of capital, leading to higher valuations in a DCF model framework.

The paper further finds that higher Alpha can be targeted by restricting investment exposure to the ESG theme combined with various style characteristics, as they display low systematic and idiosyncratic tail risks. This article from UN PRI states that best-in-class and tilting strategies using ESG scores deliver alpha and relatively lower maximum drawdowns over their respective benchmarks.

Ananth Madhavan, Aleksander Sobczyk, and Andrew Ang, in their research, break down a fund’s alpha into three categories: (1) returns from static factor exposures, for instance, the long-term overweighting of quality stocks; (2) factor timing, where managers use their judgement to regularly adjust factor exposures; and (3) individual security selection. And the authors find that the funds with high environmental scores tend to load up on quality and momentum factor stocks. The article separates the impact of ESG into “factor ESG” and “idiosyncratic ESG.” As the label implies, factor ESG is the component of fund ESG scores that is related to style factors. Idiosyncratic ESG, in contrast, reflects stock selection that is not correlated with factors The authors also discover a strong positive link between fund alpha and Factor ESG scores.

They find that factor ESG components are correlated with fund alpha, and the relationship is statistically strong. There is, however, little relationship between idiosyncratic ESG and alpha; some evidence even suggests that this relationship is negative. The article further states that investors need to be aware that ESG portfolio construction may lead to factor tilts that differ from the market as a whole. If investors don’t want these exposures in their portfolios, they will need to change their exposures to reflect this.

How can asset owners and managers navigate this issue using our SaaS platform?

ESGDS provides a technology platform to analyze ESG data and assess company and fund-level ESG performance. Our technology-enabled solutions and large team of domain experts allow us to collect high-quality, up-to-date, verified data and convert the data to meaningful analytics using our no-code dashboard. Our platform supports multiple taxonomies and methodologies and allows re-weighting of relevant risks aligned with the investor’s investment strategy and disclosure requirements.

Using off-the-shelf assessments will limit owners or managers from finding ESG out-performers

As highlighted in most of the research, investors will need to adjust factors to find ESG top performers. An “off-the-shelf” score alone won’t help with differentiation; understanding relevant issues and re-weighting of exposures is very important. Each investor has a different investment strategy, and they will need the ability to weigh issues that closely align with their values and goals.